- Home

- Michael Sledge

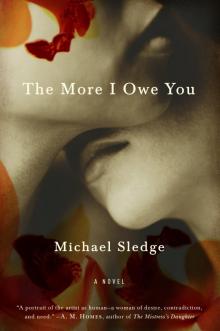

The More I Owe You Page 5

The More I Owe You Read online

Page 5

“If you’d like.”

Elizabeth crouched by the pool and slipped her hand into the water. It was colder than she’d expected. She looked upward into the trees. “Are there parrots here, too?”

“If you’d like,” Lota said softly, as if it were a promise.

The two of them fell silent. Elizabeth sensed Lota’s eyes on her. She let her hand drift in the cool water, and then she cried out in childish delight, “Look, there’s a little fish biting my finger!”

6

“Carlos,” Lota explained, “the newspaper editor, he is brilliant, a very old friend, he’s going to be president one day, I wish you’d had a more of a chance to speak with him. I shouldn’t have invited so many people, but really I had to. Rio is a noose that will strangle you. Someone is always becoming extremely offended for any reason, including myself! Sergio, of course, is the architect of my house, though most of the best ideas are my own—even he would have to admit it. He approached me several years ago because he knew I would agree to build something audacious, but I think the house has become too audacious even for Sergio. My sister Marietta, well, I’ve known her many more years than a person should have to. Did you see how she stayed in the corner the entire afternoon, not talking to anyone? Such a sour woman.”

“You do her a disservice, Lota. She’s not so bad.”

“Morsie, she’s terrible, and you know it.”

“You are not beyond being terrible yourself,” Mary said, with a surprising heat that caused Elizabeth to look down at her hands.

The lunch, in the end, had not been so excruciating. Elizabeth had to confess she’d enjoyed it. Performing the role expected of her, even here, so many thousands of miles from home, was much like lifting a boulder over her head and holding it there for an extended period: Once she’d assumed the pose, it wasn’t so difficult to maintain. Now, after many handshakes and a series of kisses upon perfumed, doughy, and bearded cheeks, the three women were alone. The house had fallen beautifully quiet. It was beginning to rain, and as the world outside grew dark, a fire was lit. At the window, a huge moth fluttered like a soft, pink hand. Elizabeth sipped the last of her limoncello, a sweet lemon liqueur one of Lota’s friends had brought from Italy, while Lota lay stretched full out upon the rug.

Her hostess continued. “The Polish couple came to Brazil during the war. They used to run the zoo in Warsaw. They showed up here with practically nothing, and now they’ve set up a business supplying animals to zoos all over the world. We’ll pay them a visit tomorrow. You have to see how they live, right among monkeys and lions, like wild beasts themselves. The two brothers, Luiz and Roberto, they are close associates of my dear friend Lina Bo Bardi in São Paulo, very interesting furniture designers. Both have a beautiful heart, very unusual for men. And both, if you can imagine, are homosexual. So unlikely.”

“Lota, please.”

“What now?”

“You know they don’t want that to become common knowledge. Not everyone lives as openly as you.”

“Well, they should, Morsie. If you don’t act ashamed of who you are, then people won’t treat you as though you should be ashamed.”

“It’s not that simple.”

“I disagree. I think it is very simple.”

Again, the private charge of emotion between the two women sent Elizabeth’s gaze to the fire. She would have liked to ask for another splash of limoncello, but after Lota had poured her glass, she’d shut away the bottle in a cabinet with a look, not unkind, that clearly indicated, That’s that. The limit set so firmly, and with so little fuss, really, avoiding any judgment, that Elizabeth felt grateful. That’s that, then. Still, the lunch had been exhausting. She’d performed well, and on the spur of the moment. She’d earned a second glass.

“Dona Fernandes was a friend of my mother’s,” Lota went on. “She’s at least a hundred years old, a devout lady, practically deaf, if you didn’t notice. I’m sorry you ended up sitting next to her. That was not where I meant you to be placed.”

“She reminded me of my grandmother,” Elizabeth said. “Whom I loved. Everyone was so interesting and accomplished. I had no idea they would all speak English. Well, all but Dona Fernandes.”

Once she’d discovered she wouldn’t have to thrash her way through three hours of monolingual Portuguese, Elizabeth had dipped into the handy pocketful of stories she’d already collected in Brazil with which she might entertain a group of strangers, charming misadventures in which she figured as the well-meaning but hapless tourist. Very quickly she’d found herself doing that embarrassing thing, a performance of herself. She might as well have stood upon a chair and proclaimed, Look at me, I can hold a boulder over my head. Once she got going, it was impossible to stop. Yet all the guests appeared to enjoy themselves. Near the end of the afternoon, as the group savored their coffees, she even let fly with the loosey-goosey story. How on earth, she asked her audience, had she been supposed to interpret Lota’s backhanded invitation? Lota had grinned; it was Mary’s flat expression that had finally reined Elizabeth in.

“Your cake, Elizabeth, was professional,” Lota said. “They loved it. Especially my sister.”

“It looks as though your sister is not too discriminating when it comes to cake.”

Lota laughed aloud. In the flickering shadows of the firelight, Elizabeth could discern the stamp of disapproval on Mary’s face.

SAMAMBAIA TOOK ITS name from a giant fern that grew in the folds of the mountain. Oh, it goes on for miles, Lota said when describing the extent of her family’s holdings. Exaggeration or literal fact, Elizabeth could not determine; aside from the handful of houses owned by Lota and her friends, there was little sign of human settlement as far as one could see across the gorgeous landscape, certainly as far as one could walk. The surrounding forest felt enchanted, home to so many plants, in an infinity of shapes and sizes, with such a variety of flowers, Elizabeth felt she would need a lifetime to learn them all. Stopping here and there along the paths, she attempted to sketch the wild entanglements of foliage. The plants clung to one another, their leaves and branches intertwined as they climbed toward the light. Buttressed trunks, serrated leaves, fuzzy or horned seed pods—each sculptural, bizarre form was a lesson in adaptation to life’s circumstance. Nearly every morning Elizabeth discovered a new bloom: a vermilion crown the size of her fist, a spidery ring of delicate green flowers. The branches of the tall trees overhead were laden with countless puffs of moss, like infants held in their arms. Elizabeth began to feel a funny tenderness, even love, for the vegetation on Lota’s mountainside, as though she carefully tended all these plants herself. On her return from these daily wanderings, monkeys scurried along the branches ahead of her, then turned back to give a high little whistle, as if to prevent Elizabeth from losing her way.

HER FIRST MORNING, Elizabeth had woken to the sound of Lota’s voice, so commanding it carried down the mountain. Instantly there was a light knock on the door, and the maid brought in a tiny china cup of coffee on a tray, as if she’d been posted in the hall to listen for Elizabeth’s first stirrings from sleep. It was not much past dawn when she emerged from her room, yet she found that Lota and Mary had already gone up to the construction site. Over the din of hammering and scraping, Lota continued to make herself heard.

Elizabeth climbed the hillside path and passed through a screen of trees. When Lota caught sight of their visitor, she set down a wheelbarrow full of rocks and, before she’d even said bom dia, ordered Elizabeth to carry it around the side of the house.

“But I’m . . .” Elizabeth protested. Not strong.

“I’ll take it,” Mary said brusquely, gripping the wheelbarrow handles.

The smile Elizabeth received was full of amusement rather than rebuke. “We’ll toughen you up,” Lota said, and placed a hand on Elizabeth’s forearm. Her eye returned to the house, but her hand continued stroking Elizabeth’s arm affectionately, as though it were a cat. All this touching! The hand placed on the arm

, the passing caress, the embraces, the smoothing of the hair, the kiss on the cheek good morning, goodnight, goodbye, hello—was the constant physical contact a Brazilian custom? Or simply a Lota custom?

Elizabeth took a seat under the trees at a worktable littered with tools. She’d brought some of her papers so that she might work alongside the other women. The morning light on the mountains was unbelievably clear and warm, the forest full of sweet aromas. She couldn’t imagine a more ideal place to write.

Yet, unable to resist Samambaia’s pull, Elizabeth kept looking up from her notebook to the black rock where clouds floated past, to the crimson bird perched at the pinnacle of a tree.

Mary had pushed the wheelbarrow full of stones inside the house. A boy mixed cement in a bucket, and Mary carefully placed each stone onto the leading edge of a wall. Nearly engulfed by her baggy work clothes, her lithe dancer’s body was apparently still extremely strong. The men had begun laying down the roof in earnest, bolting the corrugated aluminum panels along the trusses and proceeding so rapidly it appeared that in one day the idea of a house might be transformed into an actual shelter. Lota was here, and there, everywhere at once. It became like a game to locate her, to pinpoint the coordinates of the imperious voice. Each time Elizabeth did so, turning her gaze back from mountain or bird, she discovered that Lota was already watching her. Lota didn’t act as though there was anything unseemly in these intent, lingering stares, even while Mary labored like a workhorse ten feet away. Elizabeth smiled back at her hostess, and the frantic little engine at the center of her grew calm.

“What on earth will you do with all your time,” Elizabeth asked at lunch, “when the house is finally finished?”

“The house will never be finished,” Mary said. She opened her mouth as if to voice another thought, then refrained.

“Mary knows exactly how she’ll spend her time,” Lota said. “She will be busy raising her child.”

“Her child?”

“Lota!” Mary protested.

“She’s planning to adopt a baby.”

“Are you really?” Elizabeth cried, with a surge of affection for her compatriot that caused her to reach out and touch Mary herself. “You’ll be such a good mother, I just know it.” Mary might not be the sort of maternal vessel that overflowed with love and warmth, but instinctively Elizabeth knew she possessed a quality perhaps even more important: a rootedness that would make a child feel safe in the world, cared for, protected.

“I have been thinking about it,” Mary admitted, but she shook her head. “I don’t think it will happen. There’s too much going on here. I don’t have the time to devote to a child. Lota’s adopted one, so of course she thinks everyone else should, too.”

Elizabeth turned back to Lota in astonishment. “You have a child?”

Lota shrugged. It was Mary who answered. “A crippled boy she found at the mechanic’s. He was crawling around on the floor like some old car part they’d discarded.”

“That’s not true,” Lota said. “They did not want to give him up, but they knew I could give Kylso a better life.”

“But where is he now?” Elizabeth asked. “Why haven’t I seen him?”

“He’s grown up and married,” Lota said dismissively. “He’s already making children of his own.”

“What a surprising woman you are,” Elizabeth said.

Lota stabbed out her cigarette, looking pleased.

“Yes, she is,” Mary agreed. “And in other ways, entirely predictable.”

Lota stood. “Let’s go. We have much to do.”

Late in the day, Sergio the architect stopped by and was subjected immediately to Lota’s harangue on how his design of the roof could be improved, even at this late stage. After a number of unsuccessful attempts to interrupt her diatribe, he stormed off, shouting back over his shoulder that he would not return. Five minutes later Sergio reappeared, smiling sheepishly at Elizabeth and giving a shrug, as if to say, That’s just Lota. You have to love her.

ELIZABETH LOST COUNT of the passing days.

Sitting at the pool, she watched a pair of tiny brown birds chipping a hole in a decayed tree trunk, splinter by splinter, making their nest near the stream. Whenever Elizabeth came here, returning to the spot Lota had shown her their first hour in Samambaia, it was her intention to write a letter to Cal, or to draw a bit. She wanted to leave a record of this place and time. She took out her watercolors, managed a few flowers, her own shoe beside a stone. First her hand and then her mind fell still. If she’d been able to complete any of the letters she meant to write to her dearest friend, usually formidable works detailing every observation of the natural, human, and literary worlds, they would have begun and concluded with a single line.

I’m at peace.

Beside the boulder on which she rested grew a plant with long, feathery leaves. Her finger ran along the vein, and in its path the leaves gently closed. Out of her memory something very old began to unfurl. She recalled looking down, as if from a great height, into a tracery of green, a fern or other plant with leaves similar to these. She was of an age before words, gazing into the leaves while being held in the arms of someone much larger.

That was the entirety of the recollection. An image, and the shadow of a feeling.

The adult holding her could have been her mother. It comforted Elizabeth even this many decades later to imagine she might have once nestled securely enough in her mother’s arms to cast an observing eye upon the natural world. More plausibly, the arms had belonged to one of her aunts or to her grandmother.

Good thing you didn’t perish in that fire, her mother had said in the dream. She might easily have said it in life.

Her mother had not been right. That was a simple fact agreed upon by all parties, with too much evidence to be in dispute. However, the question Elizabeth had never been able to answer to her satisfaction was to what extent her mother’s abdication from all responsibility and human connection had been willed.

Too clearly, Elizabeth remembered her mother’s visits home from the sanatorium, when she, still a small child, joined the worried circle of her aunts and grandmother watching over the skittish, emaciated woman delivered to their house, more like a large, helpless infant than like a mother. How many evening meals had they endured with forced cheer while Gertrude lay on the couch emitting little squeaks and gurgles, one arm over her eyes while the other dangled to the floor, the fingers of her white hand moving as slowly as the claws of a dying crab. On one of those spectral visits, Elizabeth and her mother traveled alone from Great Village to see the widow’s in-laws at their summer home in Marblehead. Elizabeth woke in the night, not knowing where she was. Shifting light and shadows played across her bedroom wall. She smelled smoke and heard movement and bustle in the house. Afraid, she called for her mother, yet she heard Gertrude also crying out, and the voices of her paternal grandmother and aunts attempting to calm her.

A long time passed before Aunt Florence appeared in the doorway. Elizabeth tried not to whimper, though she was terribly thirsty.

Is the house on fire? she asked.

Aunt Florence told her that the fire was in a nearby town called Salem; it had spread to engulf many houses, but they were safe. The fire would not reach them here.

A low, inconsolable wail came from across the hall.

Is my mother all right?

Florence slipped into the bed and held Elizabeth close, but the contact made her turn rigid. She closed her eyes and imagined that instead of her aunt, it was her mother holding her, that it was her mother’s soft words in her ear, and only after a time of imagining this did she drift into sleep.

At early light, Elizabeth woke alone in the bed and looked out her window to see her mother in a white nightgown, drifting among people wrapped in blankets on the lawn. Gertrude smiled and spoke kind words as she brought them water and coffee, while smoke rose along the horizon.

Why had she been able to offer to strangers what she could not offer to he

r own child?

As Elizabeth sat beside the stream on Lota’s mountain, these memories no longer puzzled or disturbed or enraged her, as they had for most of her life. She sensed a new steadiness in herself, a hopefulness that had remained elusive throughout all her years of itinerancy and searching. This was not merely Samambaia working its magic upon her, she knew, not only the birds and the flowers and the mountain light. It was Lota.

7

“What is this marvelous dessert?” Carlos asked, looking down at his plate as if at the most extraordinary occurrence.

“Yes,” Lota said, “it’s highly unusual.”

Elizabeth and Mary exchanged a smile. “It’s called apple brown Betty,” Elizabeth said.

“Delicious,” remarked Carlos.

Lota said proudly, “We’ve underestimated Elizabeth’s talents.”

Carlos Lacerda was a bigheaded man with thick, brilliantined black hair, quite a bit too full, Elizabeth felt, of the importance of his own views and the sound of his own voice. She did not warm to Carlos, though Lota obviously worshipped him. Still, she understood Lota’s loyalty. She’d be the first to admit not everyone could tolerate the company of Robert Lowell, yet in Elizabeth’s eyes Cal could do no wrong.

Once the plates were cleared, it was not long before Lota and Carlos were screaming at one another. Their views were not divergent, Lota had explained; rather, they delivered into the black night a shared, unbridled outrage over the state of their country and the ongoing dictatorship. The first words of Portuguese Elizabeth began to comprehend came clear on these late nights: ditador, inflaçao, assassino. And other words, uttered by Lota, she knew she would not find in any dictionary.

Vargas will be the ruination of Brazil!

Lota’s cries reached through the house to the sitting room where Mary and Elizabeth had retired after the meal. Mary was knitting a blanket for one of Lota’s nephews, while Elizabeth sat beside a stack of books. These were the volumes produced by Brazil’s native sons and daughters that Lota had pressed into her hands—this is an extremely important text, she claimed each time she added another to the pile, to understand the heart of this country—as well as some of Elizabeth’s own favorites by Marianne, Cal, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Wallace Stevens. Early Wallace Stevens, that was; these days, she didn’t have any idea what he was talking about. Of course, Lota was already familiar with these writers, as there appeared to be no book ever published in any language that she had not devoured, from Renaissance poetry to the most recent theories on composting or septic tank function. But each night they read back and forth to one another, Lota first in Portuguese, then Elizabeth in English, and now Elizabeth was waiting for Carlos to leave so that they could begin.

The More I Owe You

The More I Owe You