- Home

- Michael Sledge

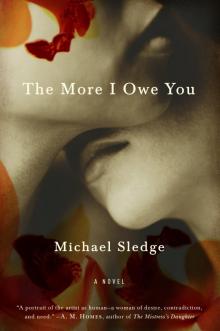

The More I Owe You

The More I Owe You Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Arrival at Santos

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Song for the Rainy Season

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

No Coffee Can Wake You

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

Copyright Page

FOR RAUL CABRA ESTRELLA

. . . O dar-vos quanto tenho e quanto posso,

Que quanto mais vos pago, mais vos devo.

—Camões

Arrival at Santos

[NOVEMBER 1951 - JANUARY 1952]

Here is a coast; here is a harbor;

here, after a meager diet of horizon, is some scenery:

impractically shaped and—who knows?—self-pitying mountains,

sad and harsh beneath their frivolous greenery,

with a little church on top of one. And warehouses,

some of them painted a feeble pink, or blue,

and some tall, uncertain palms. Oh, tourist,

is this how this country is going to answer you

and your immodest demands for a different world,

and a better life, and complete comprehension

of both at last, and immediately,

after eighteen days of suspension?

Finish your breakfast.

1

THE SHIP CROSSED the equator sometime in the night. Elizabeth sat on deck among the crates of cargo bound for South America, taking shelter from the damp wind. The sky was vast, with half a moon and masses of soft, oily-looking stars.

She was middle-aged. It was her first trip to the Southern Hemisphere.

Storms and rolling seas had followed them ever since they’d left New York. Each morning when she came up from her cabin, gray rainsqualls surrounded the freighter. They seemed to tease the ship, coming close on either side, then retreating, ahead, then behind. Among the black waves appeared glittering silver sheets where the sun broke through the clouds, roving across the water’s surface like searchlights. The captain, a reticent Norwegian, had said it was the roughest trip he’d made in years, but it was certainly not so rough as to dissuade her from lounging on deck long past midnight. Better still, not so rough that it had prevented her from working. At last she’d finished those reviews that had weighed on her mind for months.

Miss Lytton, however, had not fared as well. Seasick in her cabin most of the time, she emerged from below only at meals to attempt a few spoonfuls of broth. Poor thing, though she really was too stupid for words.

All of them, so immeasurably stupid. Miss Lytton and Mr. Richling, absolute torture to be stuck on a ship with those two. Just this evening at dinner, the petty boastings of the Uruguayan consul could not have been borne with good grace for five minutes more. The even-tempered captain had retired from table with the most brusque of good evenings. One simply couldn’t compete. The only passenger Mr. Richling didn’t successfully brutalize with narrations on the superiority of his intellect or physical courage or haberdashery was the thoroughly green and nauseated Miss Lytton. She managed to hold her own in spite of her debility, luring Mr. Richling away from the subject of himself with her own tantalizing accounts of the latest society-page improprieties, or, when she’d exhausted that topic, of the lowbrow scandals of common folk. Elizabeth supposed she should be happy the two of them had found one another. Savaging people who were not currently onboard the SS Bowplate kept them occupied and, for the most part, out of the private lives of the people who were. Tomorrow, there was to be a shipboard Thanksgiving dinner for the lot of them. The thought of that communal meal, rather than the constantly rolling ship, was enough to make Elizabeth grow nauseated herself.

I ran away into shifting weather, swaying walls. Squalls day after day.

Still, in spite of her fellow passengers, Elizabeth could imagine no more pleasurable way to travel than by sea. She could gaze at the ocean for hours and never grow tired of it. No looking forward or back, no thoughts of what you’ve taken leave of, what you hope to find when you arrive. Just this perfect suspension.

At the railing not twenty feet from her deck chair, a figure appeared out of the dark.

Recognizing the tall, angular form, Elizabeth was instantly upon her feet. When the shifting deck caused her to lose balance, she held fast to the cargo of tractors and combines. Fortunately, the hulking farm equipment was lashed down and crated, unlike the miniature vehicles constantly rolling about underfoot, endangering passengers and crew alike. The missionary had managed to teach his three young boys to speak a foreign language; was there some impediment to teaching them to put away their toys? It really could be hazardous, one’s dealings with humankind, to body and to mind.

So as not to startle her, Elizabeth softly called the elderly woman’s name.

“Elizabeth,” Miss Breen answered. The scarf she’d tied over her head was unable to contain the nimbus of white hair that floated ethereally around her angelic expression. “Why am I not surprised to find you here?”

“You’re up too, I see.”

“I’ve never been able to sleep much past four o’clock.”

“And I’ve never been able to sleep much at all.”

Miss Breen smiled in her hazy, enigmatic way. Why Brazil, Elizabeth had asked early on in the trip, why’d you decide on Brazil? and Miss Breen had answered simply, You of all people asking me that. What Elizabeth hadn’t admitted was how haphazard her own choice had been. When she’d gone to the shipping agent, intent on booking a passage to Europe, there’d been only one ship sailing on the day she hoped to depart, the Bowplate bound for Argentina, making a stop at Santos harbor near São Paulo, and so that was the voyage she’d booked instead.

“We’ve just passed over the equator, I think,” Elizabeth said. “I came on deck to see if there was any notable change.”

“And how does this hemisphere look?”

“Much the same. The fact is, one is stuck with oneself wherever one goes. Understanding myself or the world any better will not come as easily as the price of a freighter ticket.”

“No,” Miss Breen said mysteriously. “But it will come.”

“Is that the voice of experience?”

“Not at all, of hope for myself!” She added, “But then, Ida always tells me I’m a Pollyanna.”

The freighter dipped roughly to the side; Elizabeth held the railing with both hands as a laugh escaped her, of surprise and physical pleasure. She faced the warm ocean wind, inhaled the equatorial air. Where the ship split the sea, a froth of luminescence. She felt nearly a child beside the towering Miss Breen, who was willowy but not stout, probably just short of seventy, with hair so fine and billowy you wanted to pet it. Knobs of bone stuck out from her elbows. Her eyes were large and expressive, of the bluest blue. They seemed to have no age at all. One felt certain there was quite a bit more going through Miss Breen’s head than she let on to the immediate company. The few personal details Elizabeth knew—that she’d been a police lieutenant, now recently retired from directin

g a women’s prison in Detroit for over twenty years, and that she’d even played a part in solving a number of murders—had been extracted during the voyage bit by bit, after much pressing by Miss Lytton & Co. When asked the most rude and intrusive questions, Miss Breen consistently refused to lose her patience. She was extremely kind to everyone onboard, and so gentle that Elizabeth found it difficult to imagine her overseeing a stable of criminal women. A number of times, Miss Breen had referred to her friend Ida, but Elizabeth noticed it was only when the two of them were alone that she spoke of Ida as her roommate.

“Do you suppose Reverend Brown will teach his children to sing hymns on a Buenos Aires street corner?” Elizabeth asked.

“They all will sing, I imagine. Isn’t that why they’ve come?”

“Yesterday his wife asked me to read to her about Argentina from my guidebook. She knows nothing whatsoever about the place they’re going to, hasn’t read a thing about it. And I thought I was traveling in the dark. I almost feel protective of them, they seem so lost and pitiful. Though no doubt she thinks the same of me.”

“About both of us,” Miss Breen said. “We’re fallen women.” She turned her gaze upon Elizabeth, as if her blue eyes could see directly into Elizabeth’s thoughts.

They had discovered over the days, shyly and slowly, that in their daydreams they’d imagined the same Brazil, the same tapestries of green forest, the colors of birds and flowers.

“They are all more and more annoying,” Elizabeth said, with a surge of bitter feeling. “They’re more like caricatures of people than real ones—”

“Dear, it doesn’t matter.”

This hatefulness, this poison. She couldn’t escape; it had followed her out to sea. Yes, one certainly stayed what one was—that was the lesson, cross as many latitudes as you liked. Or was it possible, could she hope, that this was no more than the toxic vestiges of the last two years at last getting out of her system, like water from an unused pipe spewing rust before it ran clear? “You’re right,” Elizabeth said. “It doesn’t matter one bit, it really doesn’t.”

She and Miss Breen looked at one another.

Boldly, Elizabeth asked, “Wouldn’t Ida have liked to come with you?”

“I’m sure she would have, but she’s had to go to South Korea.”

“South Korea! So you’re both intrepid explorers.”

“She’s helping to set up a women’s police force there.”

“And you’re both in law enforcement! Your neighbors must feel extremely safe.”

“Oh, yes,” Miss Breen said, smiling, “everyone feels very safe around me.”

THE TINY CABIN was not unpleasant, but in the dark it was reminiscent of other rooms in other places where Elizabeth had felt too keenly her distance from any living being. Attempting to settle on the bunk, she was nearly tossed to the floor each time the ship pitched over a wave. Some sort of strap or bunk belt was called for. She was thankful, at least, that for once her own body, unlike the unfortunate Miss Lytton’s, did not betray her.

It was nearly dawn, yet her mind raced along with the ship’s engines reverberating through the cabin wall, surging, slowing, surging again. I’m doing well, the engines repeated, I’m doing well, I’m doing well. It was in still moments such as this that her craft showed itself to be the most useless. Why couldn’t her thoughts fill with soothing scraps, with lines and rhymes, or images she’d seen that day, the flying fish and refracted light in the ship’s spray, storm clouds, the missionary’s children in a row singing a hymn? Why could her imagination not reach, as it had so insistently when she was a child, to capture in words all the world’s unfolding marvels? Instead, her brain was in a tempest, like the rainsqualls that tossed the ship, churning in every direction, erupting with incoherent thought. A brainstorm, night after night. That’s exactly what had happened at Yaddo last year. Her mind would not alight and rest. Yaddo, the utopian dream of some mad millionairess, where the squalor of the real world was kept briefly at bay so that artists could roam at their leisure, chew their cud, and sculpt, compose, finger paint, what have you, without interruption. Elizabeth, too, had strolled the tranquil grounds, watched chipmunks scamper in the garden, fed buttered bread to the chickadees, blown soap bubbles from her balcony as an afternoon diversion, and gone quietly mad. All of it so perfect; it was only Miss Bishop that was wrong. The nervousness, the dizziness, the little splinter of panic working its way deeper and deeper—one thing alone fended them off. Each afternoon she walked past the scummy ponds and into town, directly to a trustworthy trader, then returned to her room and proceeded to drink herself numb. She slipped the bottles into the trash bin outside the kitchen, but the others knew, of course. So nice and pleasant and young, the whole herd of them, they smiled and said good morning, which was even more sinister than if they’d avoided her glance altogether. Somehow, throughout, she’d managed to keep writing, but it did not matter, not really. The weeks passed.

The night the hurricane struck, Elizabeth watched from her window as a fantastic wind uprooted the great old pines. One came crashing down across the roof of the painting studio next door. The destruction thrilled her. Then came a sharp report like a gunshot, and the wall of Elizabeth’s room lifted away from the house. A few strips of lathing stood between her and the wind and lashing rain. In her drunken state, she’d either fallen and hit her head or else been conked on the bean by a wayward piece of plaster. A draft of cold air upon her face brought her back to consciousness. Opening her eyes, Elizabeth looked directly outdoors upon the devastated scenery. It was morning now, a sky of clear blue.

Her head was in terrible pain; her decision, absolute. Elizabeth checked herself into a hospital, stayed there for a time, and that did her good. It was a start. This trip had done her even better. Since leaving New York, she’d felt stronger, saner, more productive, certainly more sober than she had in ages. She was being very good. One drink a day, that was the limit, and if she could manage, not until evening.

Dimly visible on her cabin table was the pot of white chrysanthemums Marianne had given her as a bon voyage present, still keeping after two weeks onboard. The only friend to see her off. She had to laugh thinking of Marianne’s gruff Goodbye, Elizabeth before the ship left. Elizabeth concentrated on the white flowers, which swayed and trembled with the rolling ship. They looked just like the huge foggy star visible from the ship’s deck, on clear nights, in the southwest.

SOUTH OF RIO, they sighted land. An outline of high, jagged mountains, and then, as the ship came near, ruffled green foliage on the slopes and a white knife-edge of beach. Dark clouds hovered over the coast.

After dinner, they entered the port of Santos, navigating among the two dozen big ships in the harbor. It was raining heavily, and Elizabeth went below to prepare her luggage. Before retiring for the night, she stood outside Miss Breen’s cabin door, having come with no real purpose, no offering of any sort, like a suitor without flowers.

Miss Breen filled the doorway, appearing rather monumental in the tiny cabin. Behind her stood an open trunk, half-packed, and a small dressing table with her perfumes and toiletries, neatly arranged.

“Your cabin is even smaller than mine,” Elizabeth said. “I wish I’d known. I would have asked you to switch.”

“But I’ve liked it,” Miss Breen replied. “I’ve felt as snug as a snail in its shell.”

Elizabeth thought she might have offered one of her own books as a gift, but it was such an embarrassing thing, being a poet. Thank you for living so gracefully. That’s what she would have liked to say, if you could actually say that to a person. Thank you for showing me it can be done.

In several days, at the São Paulo railway station, she will kiss the cool, powdery cheek of Miss Breen and bid her goodbye; the two women will never see one another again. But for many years, the image will remain vivid to Elizabeth of Miss Breen in the doorway of her cabin: the kind guard at the gate, inviting her to reenter the world.

BY MORNING, TH

E rain had ceased. It happened that she and Miss Breen were the only passengers leaving the ship at Santos; the rest would continue stupefying one another all the way to Buenos Aires. Misses Breen and Bishop waited on deck for the immigration officials to board. Under low, gray clouds, the harbor was full of activity, with men hauling big canvas sacks and metal drums along the wharves, and little dinghies crossing the oily water here and there, while a variety of smells assaulted the senses—diesel exhaust, coffee, and something rancid—rotten fruit, perhaps. A shark fin appeared among a pile of floating garbage, but when Elizabeth pointed it out to Miss Breen, the fin submerged in a whirlpool. The warehouses along the water were fanciful colors, pink, yellow, and blue, but the paint was faded and peeling, the buildings unkempt, some of them close to collapse. Rusted tin roofs ascended the hillside, then mountains soared up, how high she couldn’t see, their peaks were enshrouded in mist.

The sad industry of a port, a dirty and dispiriting place.

The tender was there; she saw it skirting around a ship toward them, a buoyant, battered little craft bearing the Brazilian flag, piloted by an elderly black man in a white cap.

Elizabeth gripped the railing like a bird on a branch. She wore her usual tan slacks and shirt, while beside her, Miss Breen looked elegant in a black linen dress and a scarf with blue polka dots. Why was it that a seventy-year-old prison director carried herself with greater style than Elizabeth could muster? This morning, she had discovered a scrap of paper on the cabin floor, a receipt from Macy’s in New York for $9.32, something she’d bought right before the ship had left, she could no longer remember what. She was about to throw the receipt away when she saw words on the back, in her own chicken-scratch handwriting, a note she’d scribbled in the dark the other night when she couldn’t get to sleep. Beginning of a poem—begins before the beginning—it anticipates the beginning—the act of preparation for what will come, though one doesn’t know what will come, the preparation to make a leap of faith.

The More I Owe You

The More I Owe You